Shaktikanta Das nudges India’s lenders to stop hoarding cash and start moving credit into the real economy

The Reserve Bank of India has made its stance unmistakably clear: banks sitting idle with surplus funds parked at the central bank will no longer be rewarded for their caution. Instead, they’re being handed a not-so-subtle message — lend, or earn less.

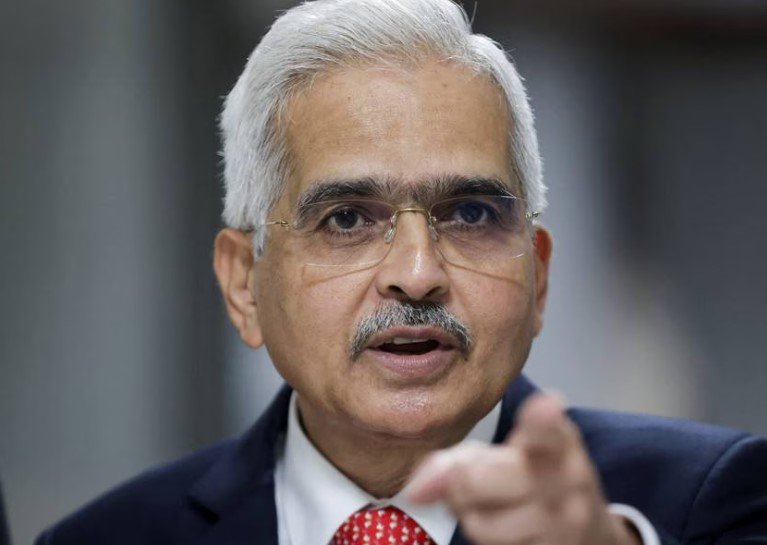

In a surprise announcement that skipped the usual fanfare of a Monetary Policy Committee meeting, RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das announced a cut in the reverse repo rate, a move aimed directly at India’s banking behavior during a fragile economic moment.

This Time, It’s Not About Repo. It’s the Other One.

The usual dance around repo rate announcements was nowhere to be seen. No MPC vote, no high-stakes deliberations. Just a simple tweak to the reverse repo — and yet, it sent a strong message.

Das’s move lowers the reverse repo rate — the interest banks earn for parking funds with the RBI — which had effectively become the main operating rate in recent weeks. Why? Because most banks weren’t borrowing from the RBI. They were parking cash.

The numbers explain it. In the wake of the March 27 cut, liquidity in the system swelled dramatically, with banks preferring the safe, easy income of the reverse repo window over lending to businesses.

One-sentence paragraph here.

RBI Is Trying to Break the Habit

Let’s call it what it is — lazy banking. And the RBI isn’t a fan.

This cut wasn’t just about nudging rates. It was about breaking a pattern. Banks, flush with liquidity, have been playing it safe. Rather than taking on risk by lending during an economic slowdown, they’ve been earning guaranteed returns by parking money at the RBI.

But Governor Das seems to have run out of patience.

“This measure is to encourage banks to deploy the surplus funds in investments and loans in productive sectors of the economy,” he said, barely hiding the frustration behind the technocratic language.

And there’s another angle too. With this reverse repo cut, the RBI is actually pushing banks into credit risk, hoping that the shift could finally inject life into the sluggish credit cycle.

Just one short line here.

How It All Works, and Why It Matters

At the heart of the move is a simple equation: lower the return banks earn on idle funds, and suddenly lending becomes more appealing.

The repo rate remains unchanged — technically. But for weeks, the reverse repo has been where the action is. Banks weren’t borrowing. They were depositing.

Let’s look at the setup in numbers:

| Rate Type | Before April Cut | After April Cut |

|---|---|---|

| Repo Rate | 4.40% | 4.40% |

| Reverse Repo | 4.00% | 3.75% |

| Marginal Facility | 4.65% | 4.65% |

And that 25-basis-point cut in the reverse repo? That’s the RBI telling banks: enough with the safe bets. It’s time to act like financial intermediaries again.

• Banks had parked over ₹7 trillion daily at the reverse repo window in April 2020.

• Credit growth was at a multi-year low.

• Even NBFCs were struggling to access fresh lending lines from banks.

Another short paragraph for rhythm.

COVID-19, Uncertainty, and the Temptation of Doing Nothing

Let’s be fair to the banks — they aren’t just sitting back for fun. With economic activity frozen and risk soaring across sectors, lenders are understandably wary.

But that caution is causing a secondary crisis: even firms with sound fundamentals can’t raise funds. The credit wheels are spinning slower than ever.

Das, in his remarks, acknowledged the risk-averse mood — but argued that this is exactly why the banking system needs to step up. Otherwise, recovery could take even longer.

Some banks say their reluctance stems from weak demand. Others point to regulatory pressure or poor asset quality. But in the RBI’s eyes, it all adds up to the same thing: too much money doing too little.

Just a one-liner here for flow.

Will This Actually Work?

That’s the trillion-rupee question.

RBI’s hope is that by narrowing the corridor between repo and reverse repo rates, it’s creating pressure. The spread between the two is now wider than it’s been in years, meaning the cost of laziness just went up.

But will banks respond?

Some already are. A few public sector banks have resumed lending to NBFCs, cautiously. Others have slashed interest on savings accounts, a move that could hint at shifting internal strategies.

Yet not everyone’s convinced.

“I doubt this will move the needle in a big way unless credit demand itself revives,” said a treasury head at a private sector bank, who asked not to be named. “You can push supply, but without demand, we’re just circulating cash.”

Short paragraph. One idea.

What Happens Next Could Reshape Indian Banking

The RBI’s decision is a shot across the bow — and one that could change how banks manage liquidity for months to come.

If credit starts flowing again, this move will be seen as the spark that worked. If it doesn’t, the RBI may be forced into more direct intervention — or even unconventional moves.

And there’s more to watch:

-

Will the RBI further reduce reverse repo if lending doesn’t pick up?

-

Could the central bank consider yield control, as seen in Japan or Australia?

-

How will banks respond if defaults rise once the post-COVID moratoriums lift?

For now, Das is betting on a behavioral shift. But he’s also watching the data — and probably gritting his teeth as he does.